How Researchers Are Responding to Mitigate California’s Wildfire Crisis

By Lisa Howard

The Camp Fire in 2018 was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California’s history, killing 85 and burning over 150,000 acres and 18,000 structures. It came just a little over a year after the devastating Tubbs Fire, signifying an alarming new reality in the state.

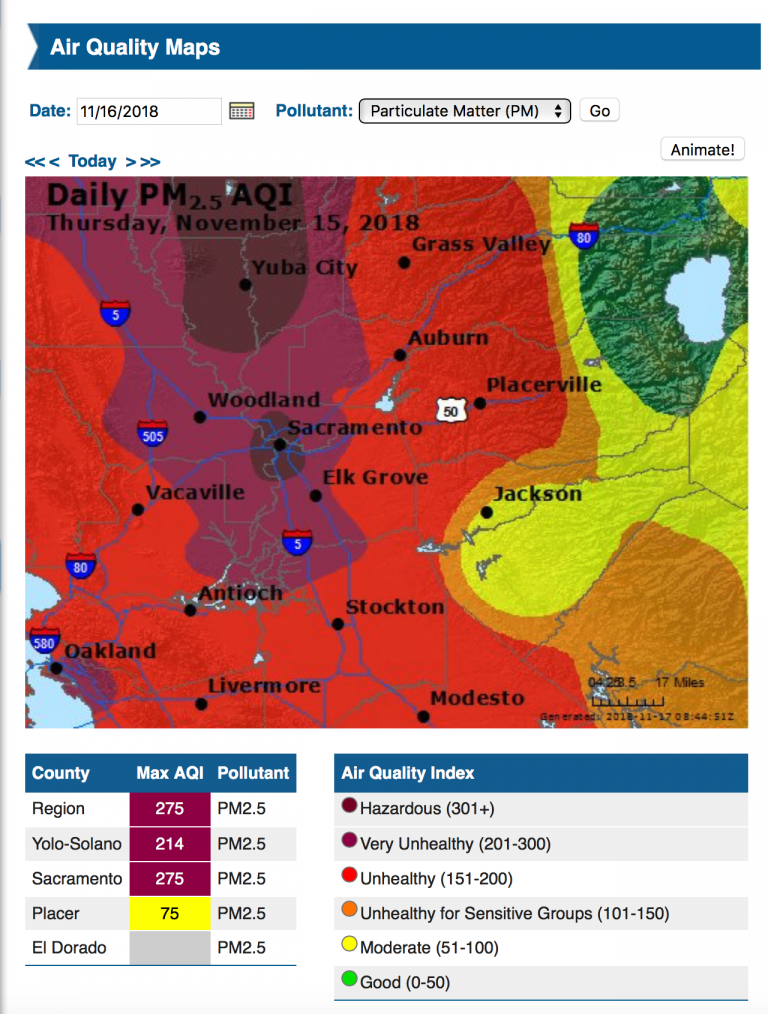

As the Camp Fire spread, the smoke blanketed most of Northern California, including Davis, for weeks. It created air quality so hazardous the California Air Resources Board recommended people stay indoors. UC Davis took the unprecedented step of cancelling classes for seven instructional days.

The rise in the destructiveness of California’s wildfires raises questions about what the future holds for the state. But what’s clear is the problems surrounding California’s wildfires are myriad and complex — and research has an important role to play in solving them.

At UC Davis, scientists and researchers are responding to the accelerating crisis with a broad range of research studies and innovations. Driven by the growing impact, they are narrowing in on ways to reduce the severity of wildfires, evaluate the toxicity of the smoke, document the environmental factors, treat the affected wildlife and understand the long-term impacts on health in order to mitigate the toll of wildfires on our lives and the planet.

Evaluating Strategies for Fuel Reduction

The lack of proper forest management has been blamed as one of the reasons for California’s deadly wildfires.

Malcolm North, who has been a forest ecologist with the USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region for 25 years — and an adjunct professor at UC Davis for 20 years — has a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and solutions.

For one thing, he points out that the most destructive fires aren’t actually taking place in the forests.

“If you look at the big disastrous fires in California, 19 of the top 20 are in chaparral, oak and woodland systems, places that are in the wildland-urban interface. That’s what the Camp Fire was, as was the Tubbs Fire and the Witch Fire. That’s a different beast entirely,” said North.

Unlike in a forest, the impact of fuel reduction in these regions is limited. “In a shrub field like chaparral, if you cut it, all of the chaparral comes back quickly. There have been good studies showing this to be particularly true in Southern California,” said North. “We have to figure out a way to harden homes and limit ignitions in these regions.”

Of the 33 million acres of forest in California, a little over half (57 percent) — is controlled by the federal government. Industrial timber companies own another 14 percent, or about 5 million acres, and state and local agencies own about 3 percent. What this means is that there are a lot of stakeholders who need and want different things from California’s forests.

Much of North’s research has focused on the ecological consequences of suppressing fire in forests as well as identifying the factors that make forests more resilient to fire and drought. His studies have revealed that the right kind of fires can be healthy for forests.

“Many types of dry forests are much healthier when they regularly have low-intensity surface fires. Most of the Native American practices with cultural burns were along these lines. It’s very beneficial,” he said.

With low-intensity burns, smaller trees and brush are thinned out, leaving larger, more established trees. Without regular low-intensity burns or thinning, North explained that a wildfire will end up burning at a very high severity, leaving very little alive in its wake.

North has also studied the amount of carbon that is lost in high-intensity versus low-intensity wildfires. Capturing carbon to reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is a key strategy for mitigating climate change. California’s goal is to be carbon neutral by 2045.

“When you see a wildfire burning, and all that gray smoky material going up into the sky, it is quite a bit of carbon going up there. The Rim Fire put out the equivalent of what automobiles put out for one year in California and did it in three weeks,” North said.

But not all fires are the same, he explained. A high-intensity fire that incinerates practically everything has a high carbon cost, but a low-intensity fire can make the forest more resilient, retaining more carbon in the long run.

North’s research has shown that a key calculation in the impact of a wildfire is how many of the largest trees were killed. “A huge portion of the carbon is concentrated in the big trees,” he said. His research shows that once you reduce the density of the forest, the carbon that remains is much more stable.

“The simple take-home is what works best for carbon sequestration also works best for the forest, which is removing the small trees and letting the big trees bask in the sunshine and grow and become healthy,” said North.

Revealing the Long-Term Effects Wildfire Smoke Exposure

UC Davis Professor Lisa Miller, associate director of research for the California National Primate Research Center, has been studying the effects of wildfire smoke for more than a decade—essentially by chance.

In the summer of 2008, wildfires in the north part of the state in Humboldt and Trinity counties burned thousands of acres, creating a thick blanket of smoke in the Central Valley.

“Based on the monitor two miles down the road, the air quality was pretty similar to what we experienced during the Camp Fire,” said Miller.

For about ten days in the summer of 2008, the monkeys living in outdoor pens year-round were exposed to levels of very small atmospheric particulate matter, known as PM2.5, that exceeded national air quality standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Miller thought it was an interesting air pollution event and began a study to assess the smoke’s impact on health.

Monkeys that were adults during the 2008 wildfires did not show any lingering effects from the wildfire smoke. “They were affected during the event because of the irritation, but three years later there was no difference in those animals relative to their unexposed counterparts,” said Miller.

When they evaluated the monkeys that had been exposed to smoke as babies, however, the differences were significant. The lungs of the three-year-old, smoke-exposed monkeys were smaller, stiffer and had less capacity than monkeys born a year later that weren’t exposed to smoke. The smoke-exposed monkeys also produced less of an immune-related protein that triggers inflammation to fight pathogens. The monkeys are now adults and are showing evidence of early interstitial lung disease.

When Miller began the study, she expected the monkeys exposed as babies to have something resembling asthma. But instead, she said it is more like pulmonary fibrosis.

And there are impacts that appear to extend to the next generation. “The animals that were born from moms exposed to smoke show a reduced immune response. That means they aren’t able to mount as robust a response as their unexposed counterparts,” said Miller.

“Wildfires have changed my perspective on what air pollution can do. Everyone has an acute response to wildfire smoke, whether you are a youngster or an adult,” said Miller. “But the long-term health impacts for the young can be severe.”

This is why she feels like protecting young lungs from wildfire smoke should be a priority. “With our research we can show why things like HEPA filters for schools should be prioritized or why there should be an emergency clean room for children,” said Miller. “Our research shows adults won’t be the ones who suffer the long-term health outcomes.”

New Approach to Monitor Air Quality During Wildfires

When the Tubbs Fire was burning in Santa Rosa in October 2017, Anthony Wexler, a distinguished professor and the director of the UC Davis Air Quality Research Center, wanted to sample smoke while the fire was happening and where it was happening. But he didn’t have a way to collect it.

The devastating fire would end up destroying more than 5,600 structures in Sonoma County and killing 22 people.

“There’s been a lot of research about wildfire smoke, but these wildfires are different because they are burning houses and structures,” Wexler explained. Traditional wildfires burn mostly biomass like trees and shrubs. But many of the recent wildfires in California are happening in what’s called the wildland-urban interface, where human development abuts undeveloped land.

“In houses there’s plastic, metal, solvents, paint, pesticides, cars in the garage made up of rubber and metal, and everything else. And in these fires, it all gets reduced to nothing,” said Wexler. “Well, nothing plus smoke,” he added.

Wexler has studied the impact of air pollution for more than 30 years. He wants to understand what’s at stake with this new type of wildfire smoke.

To find a way to get the data, to actually sample the smoke in real time, Wexler teamed with Keith Bein, an associate professional researcher also at the Air Quality Research Center.

Like Wexler, Bein’s research focuses on the health effects of air pollution. Bein had sampled smoke from the 2017 Tubbs Fire in his Oakland backyard. That gave him the idea to build a mobile air monitoring machine.

The system he created, dubbed the Rapid Response Mobile Research Unit (RRMRU), uses power from a modified electric car to run an air monitoring machine that can sample smoke in an affected area for up to 18 hours.

“The idea is that we will collect a bunch of samples and give them to toxicologists and look at the smoke’s toxicity,” said Wexler.

Bein used the mobile system to sample air from the Carr Fire in Redding in August 2018. When the Camp Fire started a few months later in November, Bein was ready. He drove to Paradise, California, to collect air samples of the potentially toxic chemicals released during the fire. But although it was exactly the time that they hoped to collect data, Bein was turned away. Only first responders and journalists, not public health researchers, were allowed to cross police lines into the fire area.

They were disappointed, but it highlighted the challenge of how to study the powerfully destructive fires that are becoming the norm in California. How can researchers gather data if they can’t access the areas where the data is?

Bein was able to collect data about the Camp Fire smoke, just not in the Paradise region. Instead, he sampled the plume for 11 days in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the wildfire created the worst air quality on record. He and Wexler also returned to Santa Rosa’s Coffey Park, which was hit by the Tubbs Fire, and sampled air pollution during the demolition, construction and renovation of the affected areas.

Bein and Wexler have since been in contact with firefighters who have agreed to help out with their research. “We are working with CAL Fire to find a safe but optimal time to gather the smoke,” said Wexler. What he does not want to do is create problems for the first responders. “We don’t want to have to get rescued,” said Wexler.

Wexler admits it feels odd to essentially be waiting for the next disaster to strike in order to collect this type of data. But he feels it’s important to find out precisely how the wildfire smoke is different in these wildland-urban interface areas, whether it’s more toxic and to determine whether it has different health effects. “Those are the big questions we need to answer.”

Developing New Treatments to Heal Burns

For UC Davis Veterinarian Jamie Peyton, it was the 2017 Thomas Fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties — at that time the largest wildfire in California history — that radically changed how she treats animal burns.

A 5-month-old mountain lion and two adult female black bears were brought to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) Investigations Lab in Rancho Cordova, California, suffering from burns from the Thomas Fire. The available treatment options were poor — burns are very painful and take months to heal, requiring frequent dressing changes.

Peyton had read about clinical studies in Brazil where researchers used sterilized tilapia skin to successfully treat burns on animals and humans. Working with CDFW and a team from UC Davis, she decided to try this novel approach, obtaining farmed tilapia skin that she sterilized and then sutured onto the paws of the mountain lion and bears.

The results of the “fish mittens” were dramatic: One of the bears was able to put weight on her injured paws almost immediately. In addition to covering the burned tissue, the fish skin helped with healing because it is rich in collagen. New skin grew back on their paw pads in a matter of weeks, instead of months.

Peyton and her team have since gone on to use the tilapia skin treatment on more than 13 different species. She is now taking the technology to help veterinarians in Australia who are coping with animals that have been injured in the country’s devastating wildfires. She hopes that healing animals with fish skin can be a game changer for treating burns because of the low cost and widespread availability of tilapia.

Modeling Wildfire Mitigation Strategies

Michele Barbato, a professor of civil and environmental engineering, had only been teaching at UC Davis a few months the day the Camp Fire broke out.

Barbato’s core research is hazards, analyzing how the load on structures — anything from houses, buildings, offices, bridges, skyscrapers — is impacted by events like earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes and fires.

“Working on wildfire was something I thought about even before moving to California,” said Barbato. “The idea was to develop fireproof material for construction in rural areas, the wildland-urban interface.”

During the Camp Fire, as smoke levels trended for days into the hazardous range, he had the idea of extending his research to include creating models for air pollution.

“What makes this wildfire smoke different from just burning wood? That was the core of the research idea. We need to investigate what is in the wildfire plume that makes it different from what’s coming from your fireplace,” said Barbato.

“The problem is a little bit bigger than just housing, so I started putting together people that had other expertise that I didn’t have myself.”

The team he gathered includes scientists from UC Davis, UC Davis Health, UC Merced, UCLA, UC Irvine, UC Berkeley, Lawrence Livermore National Lab, Los Alamos National Lab and the Electric Power Research Institute.

In November, the team’s proposal, “Assessment and Mitigation of Wildfire-Induced Air Pollution: “Mitigating and Managing Extreme Wildfire Risk in California,” received a $3.75 million grant from the UC Office of the President and an additional $1.05 million from Lawrence Livermore National Lab, Los Alamos National Lab and the Electric Power Research Institute.

“What we hope is to create a framework that allows us to investigate the effect of wildfire on health in different parts of the state, and to also project it under different climate scenarios,” said Barbato.

The team also plans to look at four different wildfire mitigation strategies — controlled burns, vegetation management, fireproof construction and urban growth policy — to see the effect of each on human health.

“That way, we will have a quantitative way of comparing different approaches that can be transformed into policy because you can actually compare what each strategy is doing,” said Barbato.

In Waking Up to Wildfires, Emmy-winning filmmaker Paige Bierma uses her camera to tell the stories of people most affected by the 2017 North Bay wildfires. We hear from survivors, firefighters, public health officials, community groups – and the scientists who are trying to make sense of it all while people struggle to recover and new fires erupt.

Legislators Chart a New Path Forward for California

California Sen. Bill Dodd’s district, which stretches from the northern part of the San Francisco Bay Area into the Sacramento Valley, was hit hard by the October 2017 Tubbs Fire. By the time the fire was extinguished, it had burned over 36,807 acres and 5,643 structures, resulting in an estimated $1.3 billion in damage.

Since then, Dodd has sponsored multiple wildfire bills. In the past two years, 11 of them have been signed into law. More are planned for the coming months.

One bill signed into law, Senate Bill 969, requires newly sold or installed electric garage door openers to be equipped with backup batteries. Widespread power outages during the Tubbs Fire meant people were unable to open their garage doors and evacuate by car to flee the flames. Of the 22 people who died in the fire, five were found where their garages once stood.

Another bill that became law on January 1 of this year, SB 209, establishes the Wildfire Forecast and Threat Intelligence Integration Center, a statewide network of automated weather monitoring stations to aid in wildfire prevention and response.

Another bill, SB 190, assists in wildfire prevention and response by increasing compliance with requirements for vegetation buffer zones.

While these and other legislative actions are being taken, the dynamics of the wildfire crisis continue to evolve, and the role research plays is becoming even more critical.

“It’s really important that researchers and policymakers have good communication because the more information we have the better our outcomes will be,” said Dodd. “There is no silver bullet, so we need to take a holistic, multipronged approach to address the wildfire risk. What makes it especially challenging is, unless we reverse global warming, the risks are going to increase.”

Climate Models Show Increase in Wildfires

UC Davis Professor Benjamin Houlton, director of the John Muir Institute of the Environment and a member of the UC Office of the President’s Global Climate Leadership Council, agrees with Sen. Dodd that a holistic, multipronged approach that connects research with policy is needed.

Houlton has modeled different wildfire futures for California as part of his climate research. He points out that nine of the top 10 largest wildfires in the state in terms of acreage have occurred in the past two decades, which correspond to an increase in temperature in the state.

“We are seeing an intensification of heat and more and more wildfires,” said Houlton. The statewide model projections, which are based on a future without global policy coordination to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, show an alarming trend.

“In the future it’s likely that we will see about a 77 percent increase in the average number of wildfires throughout California compared to baseline conditions of 1961 to 1990,” said Houlton.

And future wildfires will likely be even more extreme according to scientific analysis. “What starts to appear in the models with higher and higher frequency are mega wildfires that we’ve never really recorded. We will likely see fires that will make all the previous fires look small by comparison.”

Houlton hopes rather than just scaring people, that the projections inspire them to tackle change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“With the wildfires in California, and now in Australia, it’s becoming clear to people that climate change is causing massive amounts of human suffering. The time to address the underlying causes of these disruptions is now,” said Houlton.

“What we know is that California’s wildfires continue to grow more deadly and more destructive,” said Prasant Mohapatra, vice chancellor for research at UC Davis. “And with climate change, that trend is expected to continue. As one of the world’s major research institutions, I am hopeful that our wide range of research can not only help California but can help other parts of the world that are also struggling with the impact of catastrophic wildfires.”

Wildfires Research Work Group

The Office of Research at UC Davis recently launched an initiative to enhance interdisciplinary collaborations between researchers and connect stakeholders through a Wildfires Research Work Group. The group, which consists of more than 30 campus scientists, provides a monthly forum to identify new opportunities in research, connect specialists to build upon each other’s work and act as a central conduit for engaging with policymakers and external partners.

On April 20-24, 2020, the group will participate in the Third International Smoke Symposium, which will be held simultaneously in Raleigh, North Carolina and UC Davis. Researchers interested in learning more about the Wildfires Research Work Group can contact Ana Lucia Cordova (anacordova@ucdavis.edu) in the UC Davis Office of Research.

Media contact

- AJ Cheline, Office of Research, 530-752-1101, acheline@ucdavis.edu